Reflections from ClimateREEFS at Adaptation Futures 2025, Christchurch, New Zealand

/

Authored by Cilun Djakiman with reflections from James Rupiasa

The ClimateREEFS team took part in the Adaptation Futures 2025 conference. Our Indonesian Early Career Researcher Cilun Djakiman reflects on hers and colleague James Rupiasa’s learnings from this event.

I presented my study, “Does habitat heterogeneity predict high ecological diversity? A case study from the Philippine and Indonesian coral reef,” during the Food and Biodiversity Nexus session. My research explores how satellite derived metrics can be used to assess and monitor biodiversity in coral reef ecosystems. The findings show that benthic and geomorphic habitat heterogeneity are positively related to ecological indicators such as coral cover and fish diversity. However, these relationships vary depending on the geographical context. While the metrics worked well for Indonesian sites, they did not show clear correlations in the Philippine sites. Despite this variation, habitat heterogeneity remains a promising metric for monitoring biodiversity and identifying adaptive and resilient reefs, key elements for climate adaptation and sustainable reef management.

In addition to presenting, James, Fiona, Gino and I facilitated a session on “Narrative and Role Play” as part of the Engaging Hearts and Minds program. This activity used climate risk narratives and experiential role-play to help participants explore different perspectives on climate adaptation. James opened the session with Opa Eli’s poem, “Beta Pung Alam, Beta Pung Tanggung Jawab” (“My Land, My Responsibility”), which conveyed the interdependence between people and their environment. The poem reminded us that caring for nature is not merely a technical task, but a shared moral and cultural responsibility—one that connects us to our identity, ancestors, and future generations. Then we broke up into groups to play the Fish Game. Each group received pre-designed scenario cards, role cards (such as community member, policymaker, researcher, or knowledge broker), and storytelling props. Participants worked together as members of a fictional community facing a climate challenge. They co-developed risk narratives, proposed adaptation actions, and then shared their stories with the larger group. This collective exercise helped shape a shared vision for integrating art, knowledge, and local action in building climate resilience. Beyond its educational purpose, the Fish Game evoked empathy and emotional awareness—helping participants not only understand sustainability but also feel its urgency and complexity.

Visiting New Zealand, especially Christchurch, for the first time gave me a glimpse of what a green and sustainable city can look like. We stayed in the city centre, yet we were surrounded by trees, parks, and a beautiful garden bursting with spring flowers ready to bloom. My favourite place was the Botanical Gardens, which offered such a calm and relaxing atmosphere. The city centre itself felt peaceful, never too chaotic, and people seemed to have found a good balance between life and work. Another favourite spot of mine was Regent Street, where you can find plenty of great dining options and delicious food. And of course, having a gelato to celebrate spring, why not?

One key takeaway from my experience in AF2025 is that science alone is not enough. While scientific research provides the evidence and tools we need, it cannot create real-world impact without the involvement of policy makers. Governments often have their own priorities, which may not always align perfectly with scientific recommendations. Therefore, the challenge is: how can we align scientific insights with policy priorities so that both move in the same direction? It’s crucial to identify what is most urgently needed, what problems require immediate action, and then shape research and policy around those shared goals.

Today, there is no shortage of research. We see numerous studies, data, and findings emerging from various institutions. However, the bigger question is: how can these research outcomes be translated into practical policy guidelines? Moreover, how can this translation process be properly documented and standardized, so that successful approaches can be replicated or adapted in different regions? This is where the concept of knowledge co-production becomes essential.

During the session “The Arts of Adaptation, Communication and Education, Governance and Practice”, particularly the talk “When Knowledge Co-Production Does Not Go as Expected: Learning From the Past to Accelerate Future Adaptations”, the speakers shared valuable lessons from previous attempts at knowledge co-production. They emphasized that not all collaborations go smoothly. Common challenges include differences in personalities among stakeholders, which can lead to miscommunication or conflict, too many participants involved who do not know each other well, making coordination difficult, and stakeholders who are disengaged or not directly interested in the specific issue being addressed, for example, not caring about the ecosystem or community we are trying to protect. Some of the possible solutions that have been discussed during the plenary session was by building trust and relationships early on. Facilitate workshops or informal meetings where stakeholders can get to know each other beyond professional roles. Also, use facilitators or boundary organizations to bridge communication gaps between scientists, policymakers, and practitioners.

Adaptation can only happen effectively when multiple sectors work together, from government and academia to local communities and private industries. It requires not only shared knowledge but also active participation and coordinated action. In another session, “Experiences and Lessons Learned by Boundary Organizations on Adaptation,” we discussed how these organizations play a crucial role in linking science with policy and practice. Boundary organizations act as intermediaries, they help translate complex scientific information into actionable policy recommendations, facilitate communication among different actors, and ensure that both scientific and societal needs are met. They also help document and evaluate adaptation processes, so that lessons learned can inform future actions.

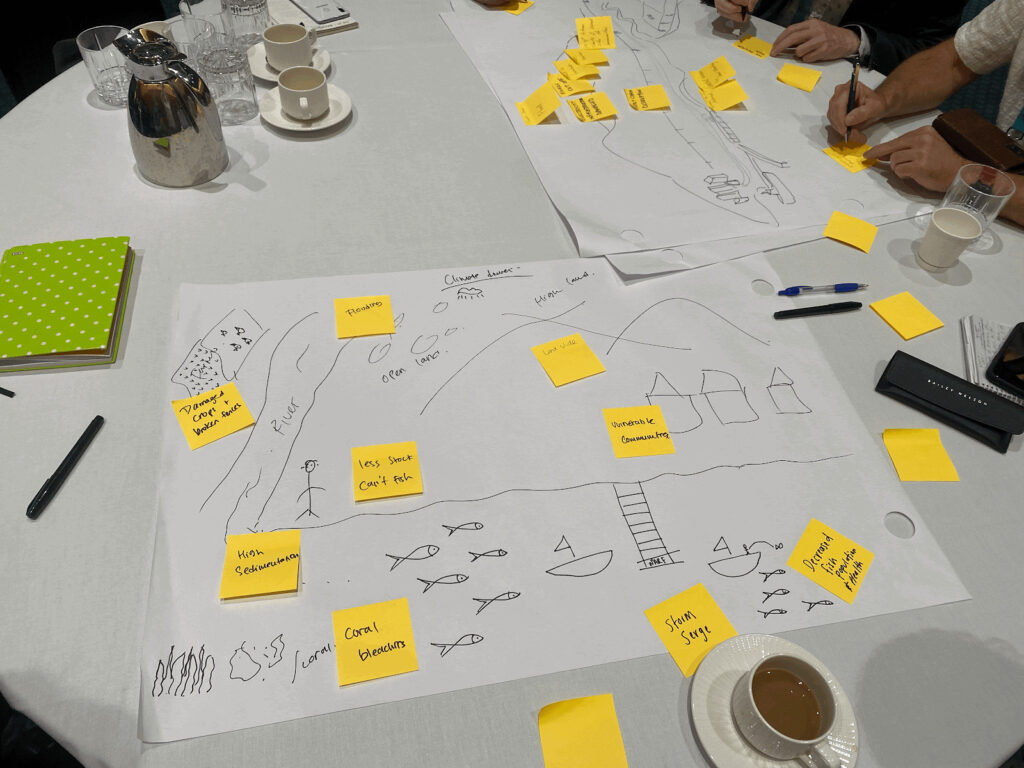

James and I also attended the session “Collective Exploration of Cascading Risk – Do Archetypes of Cascading Risk Exist?”, where we participated in a workshop focused on mapping cascading risks within specific ecosystems. Together with participants from both the business sector and government agencies, we explored how different risks are interconnected and how one event can trigger a chain of impacts across various parts of an ecosystem. This exercise was a valuable learning experience in understanding how to bridge diverse stakeholders, scientists, policymakers, and business leaders, to develop a shared understanding of climate-related risks. It demonstrated how collaboration can help identify not just environmental vulnerabilities, but also the broader social and economic consequences that stem from them. In summary, effective adaptation and governance require more than data and research; they demand collaboration, communication, and alignment of goals across science, policy, and practice.

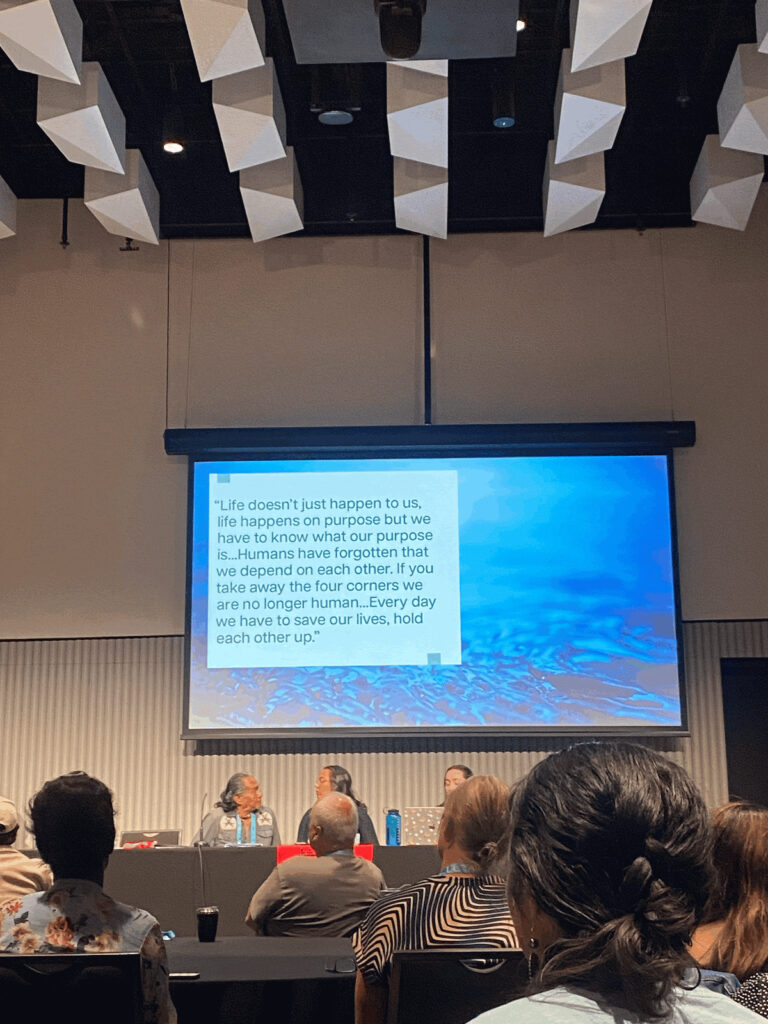

I come from a small island, Ambon Island in Indonesia, where traditional culture is deeply intertwined with the lives of local communities. During the conference, I was inspired by many sessions and discussions that emphasized how traditional knowledge is not merely an “alternative” form of knowledge, but rather a driving force behind community-led action and sustainable adaptation efforts. These communities, often on the frontlines of climate change, demonstrate how deeply rooted cultural practices can guide resilience and environmental stewardship. One session that particularly stood out to me was “Transforming First Nations-Led Climate Action, Leadership, and Governance.” It was beautiful to see how Indigenous leadership and governance structures integrate traditional wisdom with modern approaches to climate action. The session showcased how empowering Indigenous voices and recognizing their knowledge systems can lead to more inclusive, grounded, and effective adaptation strategies. Overall, my participation in Adaptation Futures 2025 reinforced the understanding that adaptation is not just about data or policy— it is about people, relationships, and shared responsibility.

Categories

Countries

CLARE Pillars

CLARE Themes

CLARE Topics

Published

CLARE Projects

CLARE Partners