Bridging Gaps in Climate Change Adaptation

/

CLARE workshop at ICIMOD | 8 October 2024

Authored by Arjan De Haan

Some 80 in-person and 80 on-line participants came together to discuss the growing gaps in climate change adaptation in Asia, and potentials to bridge these gaps. Nepal government officials underlined the need for reinforced action and support, as the devastating floods the week before again showed: adapting to climate change is a necessity, not a choice.

Experts detailed the growing needs and shared recommendations for urgently needed action: Working together, building capacity and better understanding across the finance ecosystem, with international support, and a leading role of national governments, will be critical to achieve climate and development goals.

An ecosystem in crisis

After opening comments by hosts from ICIMOD and CLARE, His Majesty’s Ambassador to Nepal and UK climate champion for the India and Indian Ocean Region Robb Fenn, underlined that we are in a climate emergency, and that we need to adapt and build resilience. He stressed: “Building resilience of communities on the frontlines of the climate crisis is of paramount importance … [and] … to enable adaptation that reduces climate risks and supports climate-resilient development, action-oriented research is needed.”

Madhu Kumar Marasini of Nepal’s National Planning Commission spoke about the strength and vulnerability of the mountain ecosystem and need to increase climate finance and diplomacy to bridge adaptation gaps to protect and restore that ecosystem. He reminded the meeting of the words of Nepal’s Prime Minister, that “mountains are tortured by rising temperatures”, and stressed that what is required is a joint collaborative effort to protect mountain ecosystems which support the lives and livelihoods of about 2 billion people.

Hon. Juddha B. Gurung, Member, National Natural Resources and Fiscal Commission closed the opening session, narrating his personal deep experience of the growing impact of climate change in Nepal. He highlighted the early work of Nepali stakeholders and experts to bring recognition of the growing climate crisis, and the efforts of Nepali activists and diplomats to raise awareness in global fora of the impacts of climate change.

Growing adaptation needs, scaling innovation

In the first session Chandni Singh, of the Indian Institute of Human Settlement described growing climate adaptation gaps in Asia, sharing with participants a first glimpse of the 2024 Adaptation Gap Report. She summarised new data and evaluation of the effectiveness of adaptation projects. Priorities for deepening work on adaptation as it emerges in the report includes focus on health impacts, climate finance, work at sub-national levels, and forward-looking risk management.

Popular Gentle, former adviser to Nepal’s Prime Minister, stressed the importance of and Nepal’s commitment to locally-led adaptation. But significant gaps exist in implementation, and he highlighted the need to enhance understanding of intersectional vulnerabilities, support for innovation in development interventions and capacity, and blending local knowledge with academic research and evidence.

ICIMOD’s Surendra Joshi completed the discussion highlighting the growing gaps in adaptation, and the need to strengthen implementation of policies and commitments. He stressed that local solutions do exist and are being piloted (such as in the HI-REAP program), and that scaling of and access to finance for these innovations are critical priorities.

Comprehensive approaches needed at address the climate finance gap

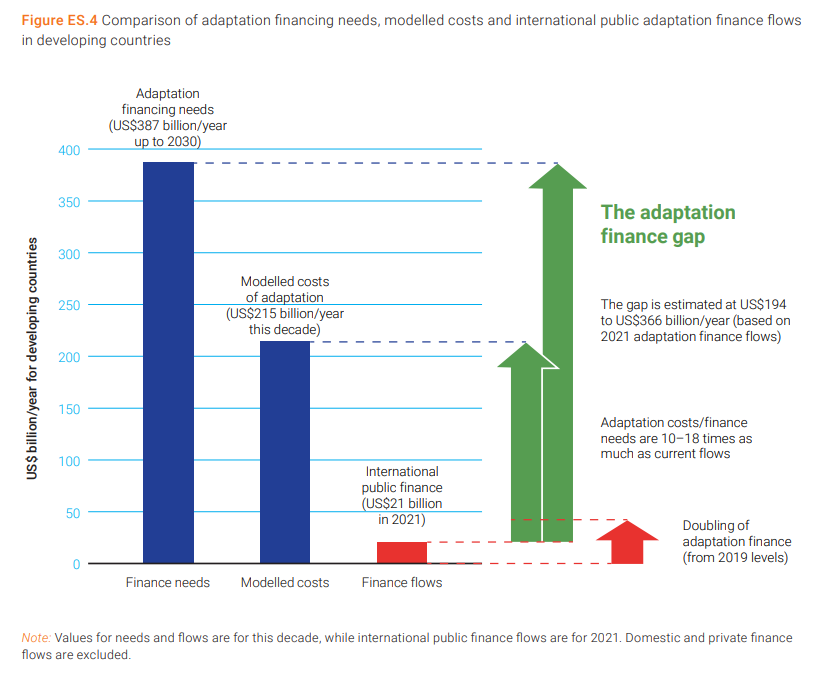

For the final session on closing the finance gap, Paul Watkiss, lead of the CLARE ECONOGENESIS project, set the scene with a warning that the news does not look good, particularly for Asia and Africa where the impacts, including economic, of climate change are most severe. As shown in the last Adaptation Gap Report 2023 and reaffirmed in the 2024 edition , climate action and particularly adaptation is underprepared and underfinanced.

- Estimated needs are much higher than current international flows

- Even meeting the Glasgow pact (doubling finance) will on reduce the gap by ≈ 5%

- A larger finance gap leads to higher loss and damage

While all numbers remain very uncertain, it is likely the total needs are even larger. The private sector also faces costs to adapt to climate change, and these costs are not included in the estimates. And as research has shown, the poor bear unequal burdens of the cost of climate change, and new models of climate finance may make this worse. This was emphasised in later discussion: the ‘quality’ of finance for climate action, particularly whether the people that most need it have access, matters as much as the quantity.

There is progress on adaptation, too. The question of climate finance is now on the agenda of finance ministries, including in Rwanda and Nepal (as ECONOGENESIS work shows), and as panelists underlined. Closing the finance gap needs innovative and scaled approaches, which will be challenging, but innovations exist.

Multiple approaches and reforms of climate finance are needed. Om Prakash Bhattarai of the Nepal Ministry of Finance reiterated how large Nepal’s finance gap is: estimates suggest this is of the order of US$ 2.1 billion or 5 per cent of the country’s GDP. Nepal lacks the means to close this gap as the country already has a large fiscal deficit, a growing debt ratio, and faces new challenges accessing finance once Nepal graduates from Least Developed Country (LDC) status in 2026.

Nepal is introducing policies and measures to address this challenge: an innovative green climate tax, the ‘Green, Resilient and Inclusive Development’ approach that included action on adaptation and mitigation, aligning budgets with adaptation needs, and guidelines to promote investments by private banks. Nepal’s government calls for much more external support to bridge the annual US$ 2.1 billion climate finance need, especially in the form of grants, as well as with simplified processes to access resources.

Partnership to scale climate finance

Ms Medinee Prajapati of Global IME Bank, Nepal, was asked how private finance can help address these challenges. Private finance institutions are investing in energy and the sustainability sectors, including agriculture. Regulators require them to allocate a part of their portfolio to these sectors and adopt sustainable banking practices. They have introduced a green taxonomy and set up units to promote sustainable banking. But, she stressed, they remain private economic actors and need to provide returns to their shareholders. Finance institutions need models of blended finance and risk or cost sharing to invest in underserved sectors. Certification of, for example, green building and climate smart agriculture is needed to avoid greenwashing.

Bedoshruti Sadhukhan, representing ICLEI – Local Governments for Sustainability was asked about the partnerships needed to scale climate finance, from the perspective of municipalities. She highlighted that municipalities in the region are developing climate action plans, but face barriers with respect to securing funding for these plans. Budget lines often do not easily accommodate new climate priorities. Local authorities cannot access global funds directly. They are dependent on national authorities to fund their priorities who themselves often lack capacities to engage in complicated funding application processes. Engaging the private sector also has challenges, as the need for financial returns may hinder investment in activities prioritized by municipalities, a gap that philanthropies can help fill.

Vivek Sen quoted CPI data that estimates available global climate finance is less than a quarter of what is needed. He argued for the need to “throw the kitchen sink” at the problem and bring in capital for long-term adaptation gains. Significant challenges exist to achieve this. Adaptation projects have long gestation periods, and it is difficult to attach a financial value to their benefits. Enabling policies or mandates to invest in small scale adaptation projects at local scales are lacking. These characteristics reduce private sector investors’ interests, and these types of local adaptation projects depend on more risk-tolerant capital (typically philanthropic).

Public investment is thus key. Blended capital structures with philanthropies supporting the longer-term investment and government finance to suppress investment risks may together create market conditions under which private capital may invest in adaptation action. Vivek concluded: “Let the government take the lead, let the private sector chip in, have a role for philanthropic capital, to finance adaptation activities”.

The discussion highlighted desirable characteristics for quantity and quality of climate finance: it needs to be additional (to ODA funding), ideally be provided in grant form, funding needs to be predictable and allow flexibility, and it needs to address poverty and inequality alongside climate change impacts. Participants felt that developed countries have a responsibility to provide resources for developing countries’ climate action, building equity and justice considerations into the planning of climate finance is critical.

Participants highlighted the need to bridge gaps between the finance and the adaptation communities, and between levels of government, as well as enhancing capacities for climate action amongst these stakeholders. Participants also stressed the need to improve coordination and communication, including understanding the perspectives and interests of private banks stakeholders.

As concluded by FCDO’s climate science advisor Dr Louise Wilson, there is an urgent need to build and grow the technical and expert capacity and partnerships. These can develop the instruments and mechanisms needed for equitable climate finance, both public and private, which is flexible and can be allocated according to unique needs. Most of all climate finance must truly reaches those who are most vulnerable and supports long term gains.

Key conclusions from the workshop

- The impact of climate change in Asia is severe and affects large numbers of people, with specific vulnerabilities for eco-systems like mountains (“tortured by rising temperatures”), and resources to address the impacts fall far short.

- Evidence for locally-led adaptation, understanding intersectional vulnerabilities, and support for innovation and scaling have a key role to play.

- Increasing international climate finance, in line with commitments under UNFCCC Paris Agreement, simplifying processes for access, and innovation in finance modalities are critical.

- The quality of climate finance is as important as the quantity: additionality, flexibility and grant-funding are central to ensure it supports local needs.

- Private finance has a role to play, but adaptation needs to be led by public interventions: “Let the government take the lead, let the private sector chip in, have a role for philanthropic capital, to finance adaptation activities”.

Categories

Countries

CLARE Pillars

CLARE Themes

CLARE Topics

Published

CLARE Projects

CLARE Partners