Gender at Work: Closing the Divide in Climate Resilience

/

Authors: Salome Okoth, Maureen Kabasa, Joel Onyango

The Climate Adaptation and Resilience (CLARE) research programme, convened the Gender Equality and Inclusion (GEI) workshop from 16th to 20th September, 2024, in Kigali, Rwanda. The workshop brought together GEI advocates, with 24 countries represented, from across the CLARE programme in an interactive peer learning format. The workshop examined diverse tools and strategies to better integrate gender equity within the Climate Adaptation and Resilience (CLARE) programme and beyond. Among the frameworks discussed, was the Gender at Work model offered insights on approaching gender inclusion from diverse multiple dimensions, from individual awareness to institutional policy change.

Exploring the Gender at Work Framework

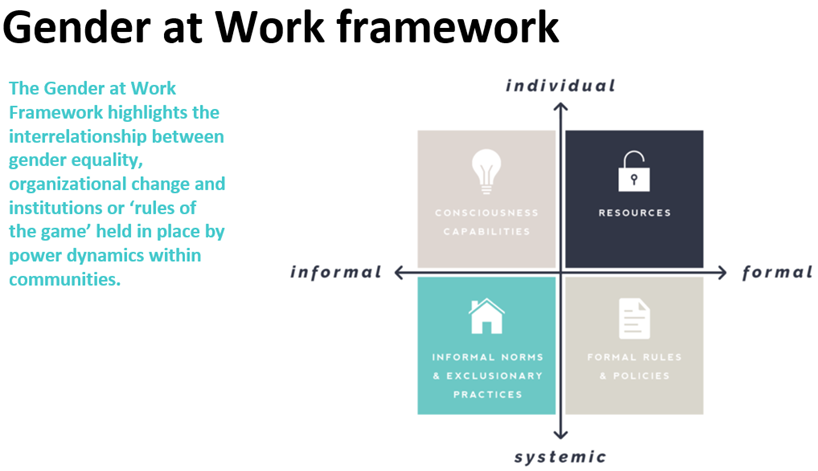

The Gender at Work framework provides a multidimensional approach to understanding gender dynamics. It does this while addressing structural, societal, and individual factors. Developed by Arundhati Rao, Joni Sandler, and Deirdre Kelleher in their work, “Is There Life After Gender Mainstreaming?” published in the journal Gender & Development in 2005, in collaboration with other gender equality practitioners and scholars, this model has been applied globally to assess and improve gender dynamics across various sectors, from organizational development to community initiatives. The four quadrants of the Gender at work model are; Consciousness and Capabilities; Resources; Informal Norms and exclusionary practices; and Formal Rules and Policies. It is through the four quadrant that help pinpoint key areas for intervention (Rao & Kelleher, 2005). Below is a visual breakdown and description of its four quadrants:

Credit: As presented by Shannon Sutton

Consciousness and Capability: The consciousness and capability quadrant focusses on individuals’ beliefs, awareness, and skills concerning gender equity. Steps towards building gender awareness through training, especially among leaders, is essential within this quadrant. The United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) emphasizes that shifting individual consciousness can help alter or change discriminatory practices within communities, a sentiment echoed in the workshop discussions on cultivating self-recovery and resilience within women. A study by Rao and Kelleher (2005) also found that individual transformation, when coupled with institutional efforts, effectively drives change within communities.

Resources: Equitable access to resources, opportunities, and support structures is foundational to this quadrant. Institutional barriers in many ways can limit women’s participation in climate resilience, with studies showing that women are often excluded from funding and decision-making in climate initiatives (Agarwal, 2018). Several examples from the participants highlighted that addressing institutional barriers ensures that women have equal access to funding, education, and leadership opportunities within their projects and places of work. This is particularly relevant in the global south context, where resource disparities can disproportionately affect women’s participation in climate adaptation efforts.

Informal Norms and Exclusionary Practices: This quadrant the deep-rooted cultural beliefs that shape gender roles within communities is examined. Patriarchal structures for example, are prevalent in many societies, such settings often limit women’s participation in climate decision-making, but research by Oxfam International has shown that community-driven approaches, such as participatory rural appraisals, can shift norms encouraging greater acceptance of women’s roles in environmental action (Huyer et al., 2015). This insight aligns with our discussions on community policing as an effective means of embedding gender-sensitive practices in climate initiatives.

Formal Rules and Policies: This quadrant addresses the formal and informal policies governing organisational and societal behaviour. Policies promoting gender equality are essential, but implementation is equally critical. Policies promoting gender equality must be complemented by training and enforcement to address gender disparities effectively (Kabeer, 2016). Discussions from participants highlighted internal Gender Equality and Social Inclusion (GESI) training as a core strategy to build institutional awareness and accountability.

Applying the Framework in Climate Adaptation

Participants were asked to map out their various activities within the Gender at Work Framework. Mapping our activities against the Gender at Work framework revealed gaps and opportunities within the CLARE projects and other areas of work. Below are some key takeaways:

Building on Existing Adaptation Mechanisms: Leveraging community resilience strategies that women already use in their daily lives was emphasized. Studies show that supporting existing structures allows communities to build on their strengths rather than adopting completely new approaches (Djoudi et al., 2016). The concept of Comic Capacities, which involve creative and community centered capacity building efforts, can support women in self-recovery while fostering collective resilience

Challenges in Applying Gender Frameworks: One challenge that came out in the discussions was the tendency to focus on institutional-level challenges, which are more visible, rather than individual-level barriers that often go unnoticed. The discussions recommended Appreciative Inquiry as an approach to capture these nuances, aligning with research by Cornwall (2016). This underscores the importance of qualitative methods in uncovering marginalized perspectives or voices, particularly in gender and climate studies.

Regional Variability in Gender Dynamics: Gender dynamics can differ greatly across regions and communities, affecting how climate adaptation strategies are implemented. Governance structures vary widely, necessitating tailored approaches rather than a one-size-fits-all strategy. African contexts for instance have unique governance structures, making uniform approaches impractical (Hicks et al., 2019). It is through this backdrop that regional agreements, such as the African Union’s Gender Strategy, provides a foundation for broader gender-sensitive policy frameworks that can adapt across diverse cultural differences while promoting inclusion

Best Practices and Overlooked Issues

Credit: Photos from the GEI Workshop field trip

The discussions on the gender at work framework sparked several best practices for promoting gender equity in climate adaptation including:

Community Policing and Engagement: Engaging communities in gender-sensitive climate adaptation helps build trust and reinforce equitable practice. Studies shows that this approach, local/community policing, has significantly contributed to addressing gender-based disparities in climate projects by empowering local voices and ensuring diverse perspectives are considered (Arora-Jonsson, 2011).

Leveraging County-Level Expertise: Utilizing local experts and culturally relevant language when addressing stakeholders helps build bridges between institutional goals and community expectations, particularly in regions where traditional gender roles are prominent (Nyantakyi-Frimpong & Bezner Kerr, 2015). This is a proven approach in some of the CLARE projects, where culturally sensitive language and appropriate terminology has been shown to improve community buy-in.

Additionally, the discussions highlighted some of the overlooked issues that often hinder gender equity efforts:

Patriarchal and Matriarchal Dynamics: Community dynamics are often shaped by gender power structures. Patriarchal and matriarchal norms can both restrict and empower gender equity and equality depending on context (Boeckmann, 2019). Changing attitudes toward these structures is essential for creating broader opportunities for both men, women, youth, children and other minorities in climate adaptation.

The Role of Media in Shaping Change: Media plays a significant role in shaping public perception of gender and climate issues. Studies from the Thomson Reuters Foundation show that framing gender and climate issues effectively can influence system-wide changes, which was a critical point of discussion in the workshop. A report by Ghosh (2020) on media’s role in gender advocacy highlights how targeted media coverage can bring overlooked issues to the forefront, reinforcing behavioral and policy changes. By reporting on gender and climate adaptation through a lens that highlights local resilience and gender equity, the media can at a great extent drive both behavioral and policy changes, amplifying the reach of these initiatives.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the Gender at Work framework has equipped us with a practical yet nuanced model to integrate gender equity within climate adaptation efforts. Applying this framework means continuously adapting our approaches to regional and cultural contexts while advocating for transformative change within communities.

The CLARE GEI workshop provided a deeper understanding of gender dynamics in climate resilience work, connecting participants with like-minded professionals and frameworks that will guide projects implementation. Addressing gender equality and inclusion is a collective journey, a journey that requires a commitment to challenge norms and foster environments where sustainable, inclusive adaptation is possible.

References

- Agarwal, B. (2018). Gender equality, food security and the sustainable development goals. Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability, 34, 26-32. Arora-Jonsson, S. (2011). Virtue and vulnerability: Discourses on women, gender and climate change. Global Environmental Change, 21(2), 744-751.

- Boeckmann, M. (2019). Examining patriarchy and matriarchy in shaping community resilience. Journal of Social Change, 11(3), 45-60.

- Cornwall, A. (2016). Women’s empowerment: What works? Journal of International Development, 28(3), 342-359.

- Djoudi, H., Brockhaus, M., & Locatelli, B. (2016). Forests, gender and climate change adaptation: a global review. Climate and Development, 8(1), 23-35.

- Ghosh, D. (2020). Media advocacy for gender equality in climate adaptation. Media and Climate Journal, 5(4), 112-126.

- Hicks, C., & et al. (2019). Strengthening governance for inclusive climate action. Environmental Science & Policy, 100, 174-183.

- Huyer, S., Twyman, J., Koningstein, M., Ashby, J., & Vermeulen, S. (2015). Supporting women farmers in a changing climate. Global Food Security, 10, 83-93.

- Kabeer, N. (2016). Gender equality, economic growth, and women’s agency: The “Endless Variety” and “Monotonous Similarity” of patriarchal constraints. Feminist Economics, 22(1), 295-321.

- Nyantakyi-Frimpong, H., & Bezner Kerr, R. (2015). Land grabbing, social differentiation, intensified migration and food security in northern Ghana. Journal of Peasant Studies, 42(2), 431-450.

- Rao, A., & Kelleher, D. (2005). Is there life after gender mainstreaming? Gender & Development, 13(2), 57-69.

- Rao, A., Sandler, J., & Kelleher, D. (2016). Gender at work: Theory and practice for twenty-first century organizations. Routledge.

Categories

Countries

CLARE Pillars

CLARE Themes

CLARE Topics

Published

CLARE Projects

CLARE Partners