Knots, Buoys, and Breakthroughs in the Coral Triangle

/

by Ben Charo, previously the program co-ordinator in conservation science at Coral Reef Alliance, now PhD candidate at the University of Rhode Island

For most of May 2024, the most important responsibility I had in my daily life may have been tying underwater knots. I was lucky enough to join the ClimateREEFS team for a three week ecological field data-gathering trip in Southeast Sulawesi, Indonesia. Our main goals were to document coral reef community diversity and collect coral samples for genetic sequencing. ClimateREEFS (Integrating Risks, Evolution, and socio-Economics for Fisheries Sustainability) is a collaboration of partners in Indonesia, the Philippines, the UK, and the USA that aims to develop techniques to identify adaptive reefs using remote sensing technologies. The ultimate goal of this effort is to develop a freely available, online tool that can identify genetically diverse reefs across the globe. The project also aims to understand gender-specific climate change vulnerabilities for community-members relying on adaptive reefs and work with relevant government bodies in Indonesia and the Philippines to support provincial and national-level marine management plans that enhance ecological and social adaptive capacity. Effective protection for the region’s reefs is critical, as it is home to 76% of the world’s coral species, and reef ecosystems support the livelihoods of millions through fishing, tourism, and coastal protection services.

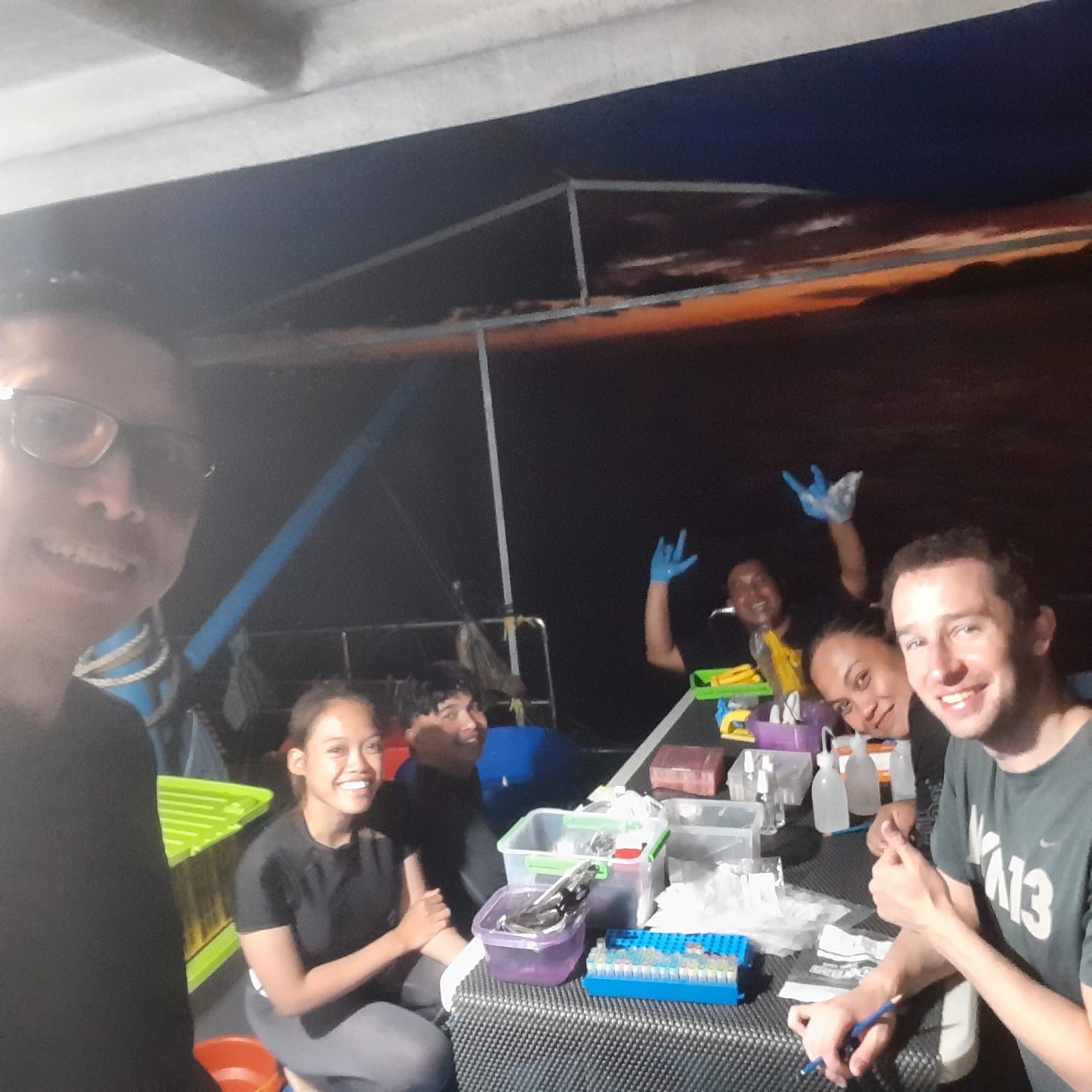

After forty eight hours of travel that took me through Tokyo and Jakarta, I finally greeted most of the ClimateREEFS team at the Makassar airport. A short flight to Bau Bau (a small city in Southeast Sulawesi) later and we were boarding the UnHas (University of Hasanuddin) Explorer, our home for the next three weeks. Though the sites we steamed to near Buton and Muna island would change almost daily, our new routine remained remarkably consistent: wake up early, eat, kit-up, take a small dinghy from our research vessel to our first coral reef transect, dive/survey fish and corals for 90 minutes, kit-down, eat lunch and store coral samples, kit-up, dive again (this time along a new transect), kit-down, chop up, carefully label, and store every coral sample (of which we eventually gathered >1000), eat dinner, finish processing samples, fall asleep (exhausted), repeat. It’s worth noting that this packed, science-focused routine would not have been possible without the tireless work of the Explorer crew, who provided us with delicious meals, assisted with organizing and preparing our gear, moved the Explorer to new sites in the dead of night, and kept things running smoothly.

I spent most of my time underwater hovering beside Prof. Maria Beger, one of ClimateREEFS’ Principal Investigators and a renowned expert on coral reef fish. Before arriving in Indonesia, I knew that Coral Triangle reefs were the most diverse in the world, but I was still shocked by the variety of creatures we encountered on our dives, even on some of the more degraded reefs we surveyed. Despite this overwhelming menagerie, Maria was, amazingly, able to recognize and identify almost every fish we saw, tallying species and estimating the size of individual fish on an underwater slate while simultaneously rolling out a transect tape—securing it to the reef as we moved along—and remaining nearly motionless in the water, progressing ahead at a snail’s pace (or in this case, a nudibranch’s pace!) to avoid frightening the fish and to allow time to mark all of them down. By comparison, my responsibilities were much simpler: stay with Maria and film the same fish using a GoPro. At the start of every dive, I was also responsible for marking the beginning of our transect with a buoy to signal where our coral gathering team should begin their work after diving in after us. The importance of ensuring our transects were kept consistent ultimately led to rapid improvement in my underwater knot tying skills, though my early attempts left a bit to be desired.

As an early career researcher (ECR), PhD student, and first-time field scientist, the experience of undertaking fieldwork was immensely educational. I gained hands-on experience with our ecological survey methods and contributed to gathering data that may inform future marine management plans and that will support my own dissertation work on coral reef fisheries and small scale fishing communities. I was also grateful for the opportunity to work with and learn from other ClimateREEFS team members about what conducting effective fieldwork consists of, from simple things like how to properly store and organize our research supplies, to managing samples, to strategically planning our itinerary, to more practical matters like how to safely move around our vessel in choppy seas. These skills are likely to come in handy later. I was also inspired by the work of other ClimateREEFS ECR’s, whose proficiency with fish identification, leadership in running our sample gathering work, poise under stressful conditions, and creativity in generating scientific ideas I hope to emulate in the future.

Towards the end of our time in the field, I was excited to help give back to the team by co-organizing a training on effectively estimating fish sizes underwater by eye. To do so, I worked with a few other ClimateREEFS team members to cut up, measure, and attach floats to over 20 PVC fish replicas (with known lengths) that we later affixed to a mock-transect on the reef at one of our last survey sites. This setup allowed all of us (including our most experienced researchers!) to calibrate their estimations of fish sizes underwater against actual measured lengths.

Though it’s been almost a year since our fieldwork concluded, I am reminded of it on an almost daily basis by email and WhatsApp notifications from collaborators, who continue to sift through and analyze our data. One of the first publications to come out of our field trip will likely concern the coral bleaching we observed across many reefs we surveyed. Though the bleaching itself was saddening to see, this paper is a good example of the creativity and adaptability of our research team. Bleaching did not factor into our initial survey plans. However, upon noticing its prevalence underwater, members of our group quickly came up with scientific questions we could ask about where bleaching was most severe (and for which coral species) and came up with a plan to incorporate it into our surveys. Now, less than a year later, this information will be submitted for publication. As more data is processed and further papers are put together, I’m excited to contribute my own research to the mix and see what other findings come out of our work.

Categories

Countries

CLARE Pillars

CLARE Themes

CLARE Topics

Published

CLARE Projects

CLARE Partners