Impact of climate change on agricultural communities in Mustang, Nepal

/

Authors: Sony K.C. and Ankur Koirala, (HiCAS, Kathmandu University)

“This year, it did not snow as expected. The Gods must be angry,” an elderly woman lamented while showing us around her apple orchard in Chhusang village in the Mustang district last month, May 2024. As picturesque as the apple orchard looked at a distance, up close the trees were sadly blighted by disease. Rampant infestations and dry leaves have meant a decline in the production of apples, leading to losses of income as well as precious time spent seeking measures to combat the disease.

A farmer in Chhusang showing diseased leaves in his apple orchard

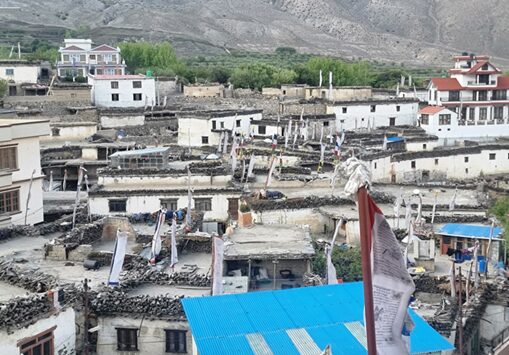

When we think of Mustang, what comes to mind is the majestic mountains, trekking trails and Buddhist prayer flags blowing in the wind. Traditionally, Mustang is also known its rich variety of agricultural products such as apples, potatoes, buckwheat, barley and various legumes. But this is changing.

The story of the elderly woman’s poor apple harvest in Chhusang village is one familiar to almost every household in the Varagung Rural Municipality of Mustang. In the past decade, there have been several reports of Mustang’s increased vulnerability to hazards such as floods and landslides. At the same time, though there is scant data, people from Mustang have been steadily migrating to cities like Pokhara and Kathmandu or even outside Nepal to countries like America, Japan and Korea. In this context, it is not always clear whether migration is driven by the changes in climate or by the aspirations of the younger generations or even both. And if it is indeed climate change driving this migration, the question of how non-migrants cope with climate change remains crucial.

As part of the research being done by SUCCESS – a project funded by CLimate Adaptation & REsilience (CLARE) program, two researchers from the Himalaya Centre for Asian Studies (HiCAS) of Kathmandu University (KU) and seven quantitative enumerators were deployed to the Rural Municipality of Varagung Muktichhetra in Mustang in May to collect primary experiences and information around these questions. The enumerators spent over two weeks conducting household surveys in more than 200 households. This Varagung Muktichhetra has five wards, (Muktinath, Jhong, Chhusang, Kagbeni and Phalyak) and was selected as a study site after extensive scoping and mapping exercises of the evident hazards. The hazards experienced in the municipality range from severe floods to more moderate hazards of untimely and unwanted rain.

An enumerator conducting an interview

The findings show the prevalence of diverse hazards associated with climate change in all five wards of the municipality. In Kagbeni, the locals reported that the most recent flood in August 2023 had drowned livestock, washed away fertile soil and caused damage to land, vehicles and houses. “Luckily, there were no human casualties but the whole event was terrifying,” said a female teacher working at a school in Kagbeni. In Chhusang, the flood of 7 years ago still haunts the memories of the locals. “The violence of the flood washed up huge rocks right in front of my home. I saw my goats being swept away right before my eyes,” recalled an elderly respondent from Chhusang.

An elderly woman from Chhusang sitting among rocks washed up by a flood 7 years ago

Apart from floods, other hazards, such as reduced snow fall and untimely rain, have left the locals, particularly farmers, despondent. Scant snowfall has led to drought and disease infestations in crops, particularly apples. “The apple production in the year 2023 declined by 50% in Jhong due to insufficient snow, the drying out of apple plants and locust attacks,” reported a respondent in Jhong.

Along with the impacts of climate change felt across these farming communities, increased migration is a phenomenon that cannot be ignored. The elderly generations have persevered to build up the land assets for generations in their villages, but the youth are now leaving. “Development has created destruction, on our climate and our young people,” stated a man in his late thirties, from Phalyak. He referred to the adverse agrarian change induced by the changing climatic conditions and youth migrating to cities and abroad. Ironically, the local schools in every ward of Varagung echo with the laughter of the children from districts like Rolpa and Rukum, as Mustang’s own youth migrate to Jomsom, Pokhara, or Bouddha, chasing education through sponsorships. Consequently, Varagung is devoid of a workforce on the farms, leading to fallow lands and low or no yields. This is a tale of a community in flux, where each departure etches a new chapter of both loss and desperate hope for intervention.

Modern and traditional housing structure of Phalyak (Ward 3)

Amidst the mounting hazards, the passion and perseverance of young ward officials in each ward deserves praise. These young officials have been proactive towards effective service delivery and accountability in their respective wards, acting as the closet guardians, information providers and support mobilizers during hazards. However, they face their own financial and technical difficulties within the offices, which in turn can affect the efficiency of the wards’ service delivery mechanisms. The local government has been able to initiate some interventions, though these are limited in scope and number and communities wait for more support. One example of intervention to combat disease infestations in the crops is the pesticide sprays which the wards provide and sell for Rs 1500 per kg. However, the cost of obtaining and using such sprays is high for elderly farmers with the added transport and labour costs for the workers they need to hire to spray the pesticide on their farms. Second, there has been a subsidised distribution of organic fertilizers in some wards to support large farm holders in the hope that they can minimise their yield losses. Despite these interventions, change in climatic conditions and increased hazards continues to disrupt traditional farming practices, reinforcing the need for further strong interventions.

Fields in Kagbeni closer to the river basins/ irrigation source

The caveat here is therefore stark. If climate change adaptation is not carefully planned to safeguard the farmers, the agrarian communities will fragment and disappear. The delicious and distinctive harvests of apples and potatoes will wither as will the legacy of Mustang. The resilient communities who have worked hard to preserve their livelihoods will see those livelihoods destroyed. This in turn could drive more migration to desolate destinations, where people are increasingly vulnerable.

As climate change is no longer a distant threat, it is crucial to encourage indigenous practices of adaptation within the communities and in parallel formulate and implement policies that are congruent to the context of Varagung. Our research has shown us that local government needs to be empowered with a better understanding of climate change and most importantly adaptation strategies to safeguard their communities and their future generations.

Categories

Countries

CLARE Pillars

CLARE Themes

CLARE Topics

Published

CLARE Projects

CLARE Partners